Like all purebred dogs, Labrador Retrievers carry a wide range of recessive genes. Many of these genes remain hidden for generations, expressed only when two carriers are bred together. When that occurs, traits that have long existed quietly in the gene pool can suddenly appear in an otherwise typical litter.

Throughout the history of the Labrador Retriever, this has happened repeatedly. Long coat is one well documented example. Tan points are another. Brindle patterning, mismarks, and other non standard expressions have surfaced from time to time in litters whose parents and grandparents were unquestionably Labradors. These traits were not considered desirable under the breed standard, so breeders historically removed them from breeding programs. There was little incentive to preserve them, no organized effort to study them, and no market pressure encouraging their continuation. As a result, their frequency declined, though they never disappeared entirely.

From a genetic standpoint, dilution is no different.

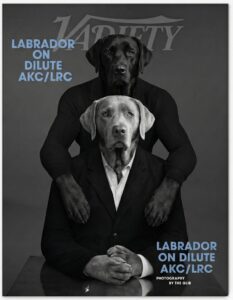

The dilute gene is a simple recessive modifier of pigment intensity. It does not introduce a new color, and it does not alter breed type. Instead, it lightens existing pigment, affecting black, yellow, and chocolate in the same way it does in many other breeds. The gene itself is well understood, widely distributed across the canine world, and not unique to Labradors.

What makes dilution different in Labradors is not biology, but culture.

At some point, public interest emerged in the appearance produced by dilution. Instead of being quietly removed from breeding programs, the recessive was intentionally retained and selectively bred. That single decision fundamentally changed its trajectory within the breed. Rather than fading into obscurity like other recessive traits, dilution persisted and increased in visibility.

This pattern is not unusual in dog breeding. Yellow Labradors were once widely regarded as undesirable and inferior to blacks. Chocolate Labradors faced decades of resistance and skepticism. Fox red has cycled through periods of acceptance and controversy multiple times. In each case, the underlying genetics did not change. What changed was breeder selection in response to shifting preferences.

Dilute Labradors followed the same evolutionary path within the breed. They were bred Labrador to Labrador, registered within the same registry, and interbred continuously with the broader population. Over time, they accumulated the same strengths, weaknesses, health concerns, and genetic bottlenecks as every other Labrador line. There is no separate population, no parallel breed, and no genetic firewall distinguishing them from non dilute Labradors.

This is where much of the modern confusion arises.

Discussions about dilution often focus on theories of historical origin, as if those theories override current population reality. But breed identity is not determined by whether a trait was once controversial or unpopular. It is determined by continuity of breeding within a closed or semi closed population over time. By that definition, dilute Labradors exist entirely within the Labrador gene pool.

Breeders are free to disagree about whether dilution should be selected for. Some will never work with it, and that is a legitimate and reasonable position. Others may choose to incorporate it with varying degrees of emphasis or restraint. What matters is recognizing that disagreement over selection does not alter biological reality.

Understanding this distinction allows the conversation to move away from accusations and toward informed discussion. It reframes dilution not as an anomaly or intrusion, but as a recessive trait whose persistence reflects human choice rather than genetic exception. That clarity is essential for any productive conversation about standards, stewardship, and the future of the Labrador Retriever breed.