Charcoal Labradors: What the Conversation Gets Right and Where It Still Goes Wrong

Recent articles above discussing charcoal Labradors are a welcome step forward. They correctly affirm that charcoal Labradors are registered Labrador Retrievers, that their coat color is caused by the recessive dilute d gene, and that temperament, trainability, and family suitability are not determined by coat color. Those points matter and deserve acknowledgment.

However, several misconceptions continue to circulate, often unintentionally. If the goal is genuine education rather than recycled controversy, those misconceptions warrant clarification.

1. The Dilute Gene Is Not “New” and Its Origins Are Often Oversimplified

Much of the controversy surrounding charcoal Labradors rests on the assumption that the dilute d gene is a recent or foreign addition to the Labrador Retriever. That assumption is far less certain than it is often presented.

Two primary origin theories are typically cited.

Theory A: Historical Outcross Introduction

One theory proposes that the dilute gene entered the Labrador population through the offspring of a Weimaraner cross. This claim is largely based on visual similarity and the known presence of dilution in Weimaraners. While frequently repeated, this theory has never been substantiated by consistent genomic evidence demonstrating shared Weimaraner haplotypes across the broader dilute Labrador population.

Theory B: Foundational Breed Origin

A second and arguably more plausible theory is that the dilute gene existed within the Labrador gene pool from the beginning. Early Labradors trace their roots to working water dogs from Newfoundland. Those foundational dogs share ancestry with breeds such as the Newfoundland and the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. Notably, both of those related breeds carry the dilute gene naturally. This makes it entirely reasonable that dilution existed at low frequency within early Labradors long before modern genetic testing or formalized breed standards.

Why the Origin Debate Is Largely Academic Today

Regardless of which origin theory one favors, the modern genetic reality is the same. Dilute Labradors have been knowingly bred within a closed Labrador population for nearly fifty years. Through repeated backcrossing within Labradors, any residual genetic contribution from a hypothetical origin dog would be functionally diluted out over generations.

What would remain, if anything, would primarily be the recessive dilute gene itself. The rest of the genome is overwhelmingly Labrador Retriever by structure, behavior, temperament, and function.

2. Visual Similarity Is Not Genetic Proof

Charcoal Labradors are often visually compared to Weimaraners. Coat color alone, however, is not evidence of recent shared ancestry. The same dilution mechanism produces similar appearances across many unrelated breeds. Confusing phenotype with pedigree is a common error in popular discussions of genetics.

Claims that charcoal Labradors resemble hounds or Weimaraners more than other Labradors are subjective and vary widely by individual dog, breeding line, and selection priorities. Structure, head shape, ear length, and body proportions are influenced by selective breeding within Labradors themselves, particularly across working and show lines, not by coat color.

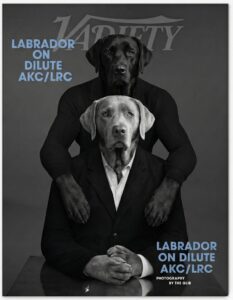

3. AKC Registration and Color Coding

Charcoal Labradors are typically registered as black Labradors with the AKC. This is not because they are “secretly” something else, but because the AKC registers dogs based on parentage rather than coat color genetics. Color codes function as administrative identifiers, not declarations of genetic status. The AKC has made a public and consistent registry decision to instruct breeders to register dilute Labradors under their base coat color. There is nothing nefarious about breeders complying with the requirements of the registry. If additional color designations were available, more precise reporting could occur, but the current system reflects policy, not deception.

It is also accurate that charcoal Labradors are not eligible for conformation showing under current breed standards. That exclusion reflects club policy regarding color, not a determination of breed purity or function.

4. Dilution Does Not Equal Disease and the Gene Is Not Going Away

The dilute d gene is sometimes associated with follicular dysplasia, a condition that can affect coat and skin quality. It is important to state clearly that this condition is not universal among dilute dogs, varies significantly by breed, and is strongly influenced by overall breeding practices rather than color alone.

Just as important, there is no practical way to “turn back the clock” on the dilute gene within Labradors. Whether one believes the gene entered through historical outcrossing or existed at low frequency from the beginning, it has now been present and knowingly bred within the Labrador gene pool for decades. At this point, attempts to remove it entirely are neither realistic nor constructive.

The more productive question is not whether the dilute gene should exist, but how it can be responsibly and respectfully managed within the breed. That includes thoughtful mate selection, avoiding high risk pairings, prioritizing comprehensive health testing, and selecting for sound structure, coat quality, and overall robustness.

Continued controversy does little to improve canine welfare. A focus on evidence based breeding decisions and whole dog health offers a far better path forward than attempting to litigate the past.

5. Breeding Responsibility Matters More Than Color

The Largest Myth to Bust: Color Outside the Standard Does Not Equal a Bad Breeder

One of the most persistent myths in the charcoal Labrador debate is the assumption that breeding a color outside the written standard automatically makes someone a backyard or irresponsible breeder. That conclusion does not logically or ethically follow.

Breeding quality is determined by practices, not pigment. Responsible breeding is demonstrated through comprehensive health testing, transparent pedigrees, thoughtful mate selection, genetic diversity management, sound structure, stable temperament, and a commitment to the long term welfare of the breed.

Conversely, poor breeding practices can and do exist within standard colors. Producing yellow, black, or chocolate Labradors alone does not guarantee ethical breeding any more than producing a dilute Labrador automatically negates it.

The focus should remain where it belongs: on whole dog evaluation rather than single trait exclusion. When health, function, temperament, and integrity guide breeding decisions, color becomes a secondary consideration rather than a moral verdict.

If the shared goal is stronger, healthier Labradors, the conversation must move beyond labels and toward evidence based standards that apply equally to all breeders, regardless of color preference.

Moving the Conversation Forward

Charcoal Labradors are Labradors. They retrieve, bond deeply with families, thrive in working and companion roles, and succeed when bred and raised responsibly. Continued discussion is healthy, but it should be grounded in genetics, evidence, and consistency rather than assumptions based on appearance or rumor.

If the goal is better dogs, the path forward is not exclusion or caricature. It is transparency, testing, and integrity in breeding decisions.

That is something all Labrador people should be able to agree on.