In the modern dog world, the word purebred is often treated as sacred. Fixed. Immutable. As if a breed emerged fully formed and untouched by human preference.

That belief is comforting. It is also historically false.

Every recognized dog breed exists because humans selected, excluded, emphasized, and recorded traits they valued at a specific moment in time. What we now call “purity” is not a biological constant; it is a human decision backed by paperwork. Understanding how breeds are “made” is essential to understanding where the Labrador Retriever is today and why the presence of Silver Labradors is not an anomaly, but a predictable stage in breed evolution.

What Does “Purebred” Actually Mean?

Biologically speaking, no dog is “pure.” All domestic dogs are Canis lupus familiaris. In kennel club terms, purity simply means a closed studbook.

A dog belongs to a closed studbook when its lineage is recorded and traceable for a defined number of generations. That is it.

- Purity is not ancient.

- Purity is not a moral status.

- Purity is a snapshot in time.

The moment a studbook closes, everything inside becomes “pure” by definition, and everything outside becomes “impure”—regardless of genetic similarity or functional ability.

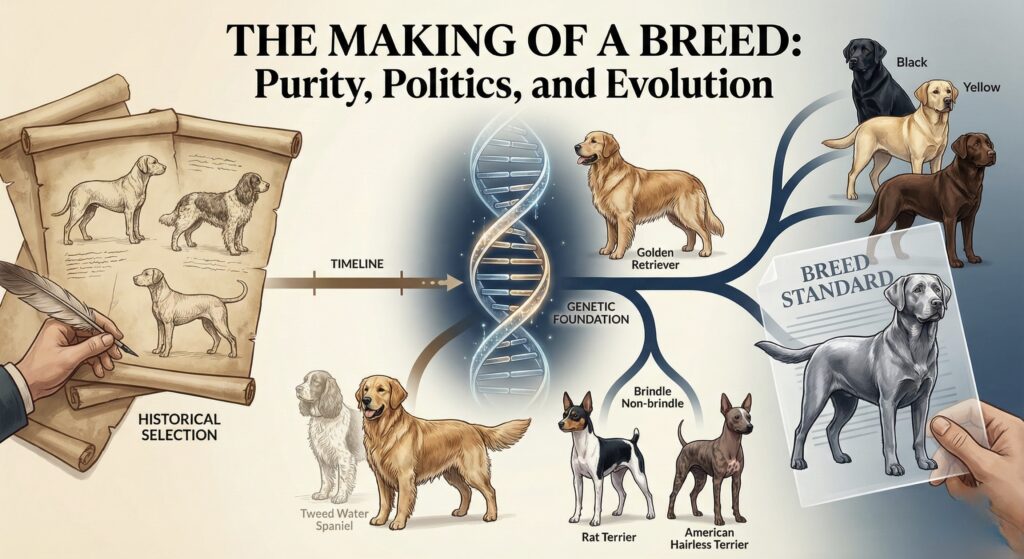

The Golden Retriever Example

The Golden Retriever is widely viewed as a classic, “pure” breed. Yet, it was intentionally created in the late 1800s by crossing Flat-Coated Retrievers with the now-extinct Tweed Water Spaniels.

Once breeders achieved a consistent look, the registry closed. From that moment forward, those dogs were “purebred” Goldens, and their mixed-breed ancestors were quietly erased from the narrative. The dogs didn’t change; the paperwork did.

Breed Standards Are Political Documents

A breed standard is not a scientific paper; it is an aesthetic and philosophical manifesto written by a parent club. This is where human politics—preferences, likes, and dislikes—dictate the future of a gene pool.

The Rat Terrier and the American Hairless Terrier (AHT)

These two breeds share the exact same genetic foundation. They diverged because of a human disagreement about “the look.”

- The AHT community chose to embrace brindle and various skin patterns.

- The Rat Terrier community disliked the appearance of brindle and wrote it out of their standard.

Today, two dogs with shared DNA and shared ancestry are judged differently because of a human preference encoded into a rulebook. The dogs didn’t change; the standard did.

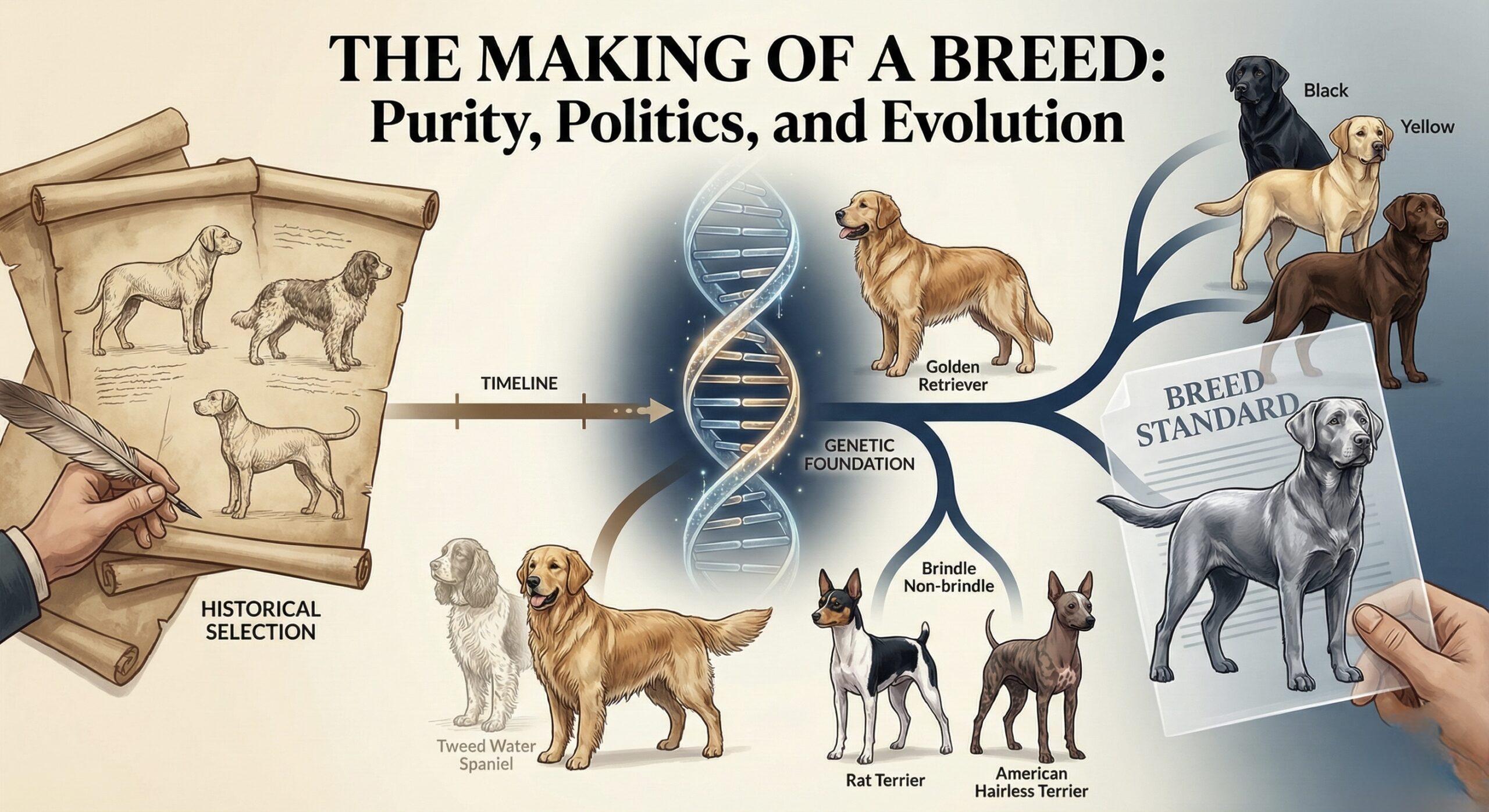

The Labrador Standard and the Dilute Gene

The Labrador Retriever standard was written long before modern canine genetics existed. The preference for Black, Yellow, and Chocolate was an aesthetic choice formalized in the early 20th century. At that time:

- The dilute gene (which creates the silver/charcoal color) was poorly understood.

- DNA testing did not exist.

- Documentation was incomplete.

What followed was not a scientific verdict, but a cultural one. Silver Labradors were sidelined not because they were proven to be “unhealthy” or “foreign,” but because they did not align with an aesthetic decision made 100 years ago. Just like the brindle Rat Terrier, a naturally occurring gene became “politically undesirable.”

The High Cost of Closed Populations

When we treat a breed as a “finished product” frozen in time, we create a False Dichotomy: that we must choose between “preserving the breed” or “allowing dilution.”

In reality, true preservation requires population awareness. When breeds are tightly closed around narrow aesthetic preferences, genetic diversity shrinks, inbreeding rises, and disease risk accumulates.

Preservation without genetic diversity is simply the preservation of decline.

Silver Labradors force a necessary conversation: Are we protecting a breed (its health, heart, and function), or are we just protecting an image?

The Silver Labrador as a Modern Evolution

Silver Labradors are not a rebellion against the Labrador Retriever; they are a continuation of its history. They are:

- Registered and documented.

- Bred intentionally for temperament and health.

- Evidence of the breed’s natural genetic depth.

What makes this moment contentious is not biology—it is timing. Standards reflect the values of the people who write them. As science advances, standards eventually follow. They always have.

Purity records the past. Standards choose the future.

The Path Forward: Responsibility Over Secrecy

For the Silver Labrador community, the goal isn’t to change the past, but to document the present.

- Register dogs accurately.

- Maintain meticulous pedigrees.

- Health test aggressively.

- Breed for temperament first.

History favors those who keep the best records. Every breed was once “new,” every standard was once “controversial,” and every definition of purity was once undecided. The Labrador is a living population, and Silver Labradors are proof that preservation and progress were never enemies to begin with.