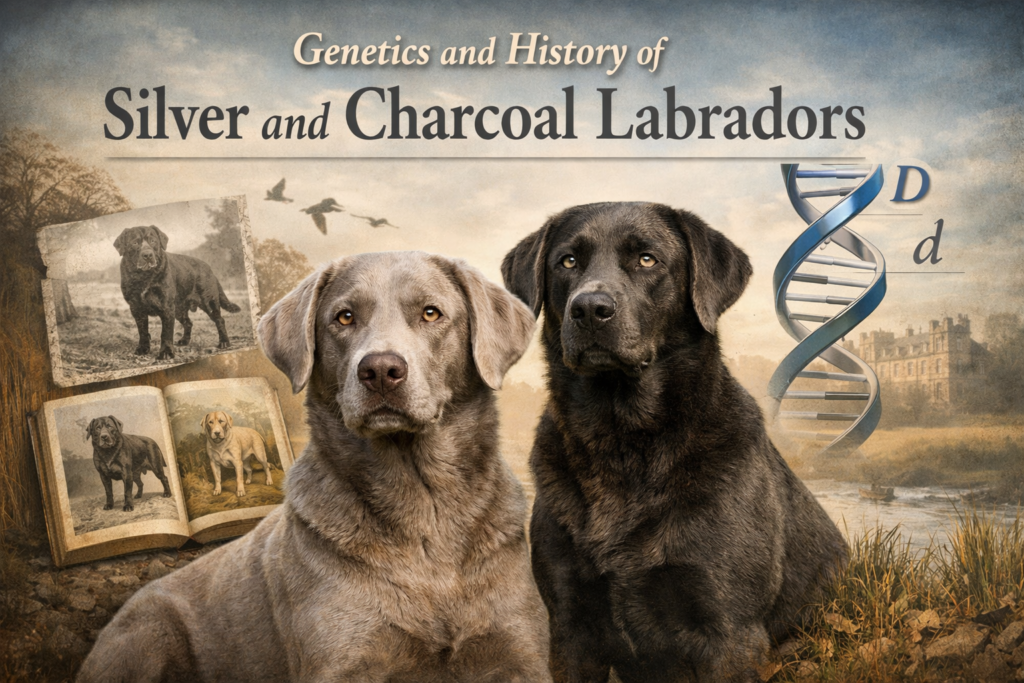

Silver and charcoal Labradors are among the most visually striking dogs in the breed, and their appearance has made them a persistent subject of debate. Admired by many and opposed by others, they occupy a controversial space within the Labrador community. Understanding why requires separating breed history, genetics, and registry policy from rumor and assumption.

The Origins of the Labrador Retriever

Like all modern breeds, the Labrador Retriever did not emerge fully formed. Its roots trace back to Newfoundland, where working water dogs were bred for retrieving and fishing. The St. John’s Water Dog is widely recognized as a primary predecessor, valued for function rather than appearance.

When these dogs were exported to England in the nineteenth century, selective breeding gradually refined them into what we now recognize as the Labrador Retriever. The breed was formally recognized by The Kennel Club in 1903 and by the American Kennel Club in 1917. Early Labradors were predominantly black, largely due to breeder preference rather than genetic limitation.

Other colors emerged over time. Chocolate Labradors, which require two recessive copies at the B locus, gained acceptance in the 1930s. Yellow Labradors followed a similar path from rarity to widespread acceptance. In each case, the genetics existed long before the colors became fashionable.

Why Dilution Is Different in Perception, Not Genetics

Dilution does not create a new color. It modifies pigment intensity through a recessive allele at the D locus. Dogs with two copies, dd, express dilution, producing silver from black or chocolate backgrounds and charcoal from black with yellow factors. Dogs with one copy, Dd, are carriers and show no visible difference.

Because carriers are indistinguishable from non carriers, dilution can persist quietly for generations. This is standard recessive inheritance, not evidence of recent introduction.

References to dilute appearing Labradors date back at least to the 1950s, including mentions in sporting publications such as Gun Dog magazine. These references predate the commonly repeated claim that dilution originated from a Weimaraner cross.

The Weimaraner Myth and Registry Reality

The idea that silver Labradors originated from Weimaraner crossbreeding gained traction in the late twentieth century, particularly during the 1980s. Despite its persistence, this claim has never been supported by documented breeding records, nor is it required by genetics.

The dilute allele is widespread across dog breeds and does not require crossbreeding to appear. Its presence in Labradors follows the same inheritance patterns seen elsewhere.

Registry policy has added confusion rather than clarity. Neither the AKC nor The Kennel Club recognizes silver as a distinct Labrador color. In the United States, silver Labradors are registered as chocolate, while charcoal Labradors are registered as black. In the UK, diluted Labradors may be registered but are typically marked as non recognized for show purposes.

These are administrative decisions, not genetic disqualifications. Historical AKC reviews found no evidence invalidating the purebred status of dilute Labradors that met pedigree requirements. Registration therefore continued under existing color categories rather than exclusion.

Health Considerations and Responsible Breeding

Claims that silver or charcoal Labradors are inherently less healthy are not supported by genetics. Dilution itself does not determine health outcomes. While color dilution alopecia, a hereditary skin and hair follicle condition, has been reported in dilute dogs of many breeds, including Labradors, its occurrence is variable rather than universal.

There are no Labrador specific studies demonstrating a high prevalence of CDA within the breed. Available evidence suggests reported cases represent a relatively small subset of dilute Labradors. This mirrors patterns seen in other dilution expressing retriever breeds. Chesapeake Bay Retrievers routinely express dilute brown tones through the same D locus mechanism, yet CDA is not considered a defining or widespread health concern. Newfoundlands have also historically carried dilution variants without population level impact.

These comparisons indicate that dilution alone is not predictive of disease. As with many inherited traits, clinical expression appears influenced by broader genetic context and line specific factors rather than the dilute allele itself.

Responsible breeders prioritize comprehensive DNA screening and orthopedic evaluations such as OFA and PennHIP. These practices matter far more than coat color. Poor breeding practices can produce unhealthy dogs in any color.

Why the Debate Persists

The controversy surrounding silver Labradors is not rooted in genetics, but in tradition and selection philosophy. Dilution persisted because it was invisible when carried and later selected intentionally once demand emerged. This mirrors the historical path of other once controversial traits within the breed.

Silver and charcoal Labradors are best understood not as anomalies, but as recessive expressions that have existed within the Labrador gene pool and became visible through ordinary inheritance and human preference.

Genetics does not respond to controversy. It responds to inheritance.

A Registry Moment That Revealed the Real Issue

In November 2025, the AKC briefly introduced a distinct registration color code for Silver Labradors, code 574, following input from the Labrador Retriever Club. The move was framed as an effort toward greater accuracy and transparency, implicitly acknowledging what had long been true: dilute Labradors already existed but were being recorded under incomplete color labels.

The policy quickly exposed a contradiction. Only silver received a separate code, while charcoal and champagne remained unrecognized and continued to be registered under black or yellow. If accuracy was the goal, selectively recognizing one dilute expression made little sense.

The reversal came swiftly. Following backlash from segments of the conformation focused show community, the Labrador Retriever Club withdrew its support, and the AKC removed the Silver code from active use. This decision was not driven by new genetic evidence, pedigree concerns, or findings that silver Labradors were anything other than purebred. The science did not change. Politics did.

For many dilute breeders, this episode confirmed long held concerns. The brief adoption and rapid revocation of the Silver code appeared less like principled transparency and more like optics management. By isolating silver while leaving other dilute expressions untouched, registry actions raised legitimate questions about administrative separation rather than honest documentation.

The episode did not resolve the debate. It exposed it.