Critics often claim that dilute (Silver/Charcoal/Champagne) Labradors are the result of recent, unethical crossbreeding.

However, history tells a different story—one of shared ancestry and open stud books.

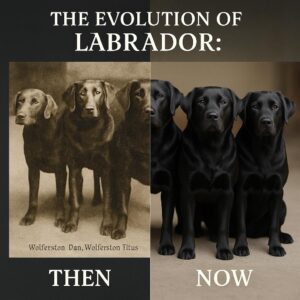

1. The Common Ancestor

It is historical fact that the St. John’s Water Dog (Lesser Newfoundland) is the foundation stock for all modern retrievers. This single breed split into several lines, including:

• The Labrador Retriever

• The Chesapeake Bay Retriever

• The Newfoundland

2. The Genetic Evidence

We know for a fact that the Chesapeake Bay Retriever and the Newfoundland both carry the dilute (d) gene naturally.

• Logic dictates: If the parent breed (St. John’s Dog) passed the dilute gene to the Chesapeake and the Newfoundland, it is genetically consistent that it also passed that same gene to the Labrador.

3. The “Open” Stud Book Era (The Smoking Gun)

The most distinct proof lies in the breeding books.

• UK: The Kennel Club did not close the Labrador stud book until 1903.

• USA: The AKC stud books remained open until 1917.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, breeding was based on performance, not just pedigree. It is well-documented that early breeders frequently crossed Chesapeake Bay Retrievers into Labrador lines to improve coat density and water drive.

The Conclusion?

The dilute gene wasn’t “snuck in” by Weimaraners in the 1950s. It was woven into the Labrador’s DNA over a century ago by the very founders of the breed, through the St. John’s Dog and legitimate crosses with our Chesapeake cousins during the open stud book era.

The gene has always been there—hidden, recessive, and historical.